(Editor’s Note: While I don’t believe I’ve spoiled this movie, there may be an element or two you’d want left to discovery. So, if you haven’t seen the movie I’m talking about yet, it might be best to go ahead and do that first.)

I’m one of those people who believes the best art comes from darkness.

Artists who find themselves dealing with dysfunction, mental health issues, personal tragedy, and other forms of negativity need ways to channel those feelings of loss and hopelessness. Turning that pain into song is a great way to channel those feelings. Artists like Elvis Costello, Aimee Mann, and Michael Penn spring to mind.

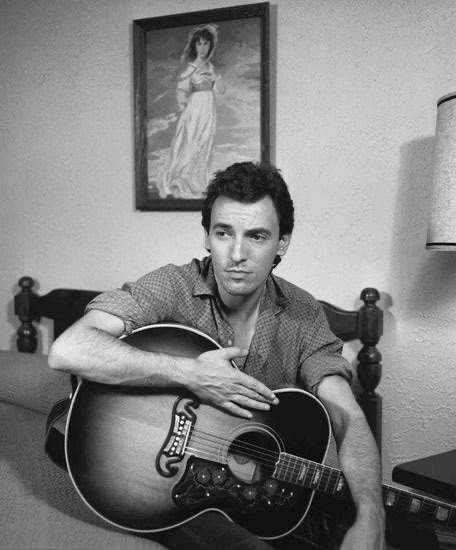

While I consider myself a casual fan of his music, I didn’t know much about Bruce Springsteen as a man. I finally got around to watching Springsteen: Deliver Me From Nowhere, a movie based on the artist’s life.

The movie, starring Jeremy Allen White, is not a biopic proper (where we learn about the subject from birth to the present). Rather, it is an examination of Springsteen’s past (focusing on a difficult relationship with his father), present (where he tries to reconcile with the possibility of a long-term relationship with a woman), and potential future (where his label, Columbia, is eager to follow up the highly successful album The River with a new album full of hits). Through it all, Springsteen creates a stark, melancholic album called Nebraska, which is the polar opposite of what his label wanted and what was expected of him.

The movie is decent. Springsteen fans will no doubt dig it. Casual or non-fans may find it a little wanting. Allen does a solid job of playing Springsteen (who was around during the film’s prosecution), including singing and playing guitar. The movie also gets credit for being largely accurate, save for the love interest (who is a composite of a few women Springsteen was seeing at the time).

The most important truthful element covers Springsteen’s issues with mental health, which manifested itself in the form of depression. His father is portrayed as an abusive bully, his girlfriend was demanding to take things to the next level, and Columbia was eager to turn Springsteen into a superstar.

Fortunately, Springsteen had support systems in place. His mother served as a buffer from the family drama; his producer and friend Jon Landau ran interference against Columbia; and Nebraska helped Springsteen channel some of his demons. This is where the “art from pain” theory comes into play.

The sessions that yielded Nebraska also produced “Born in the U.S.A.,” which — like the rest of Nebraska — was recorded by Springsteen alone in a bedroom on a four-track cassette studio recorder.^ According to the film, Springsteen wanted “Born … “ to sound bigger and more bombastic, which he could accomplish with his E Street Band. But that approach wasn’t working for the other Nebraska material.

The songs recorded in that bedroom were stories of sadness, frustration, and crime. They came from the dark side of Springsteen’s personae. To add his band — which was attempted — would bury the music’s true meaning. Springsteen’s solution to this dilemma was to shelve the band-based material and release the four-track recordings as-is. Furthermore, he refused to promote Nebraska, and demanded the same from Columbia. And there would be no tour to promote the record. Nebraska would just be out there, period. The world could do with it whatever they desired.

Naturally, the label pushed back. But Springsteen held his ground (with help from Landau), and Nebraska went on peak at number three on the album charts. The band-driven material became the album Born in the U.S.A., which catapulted Springsteen into superstardom.

Like so many casual fans, I was aware of Springsteen’s existence. “Born to Run” was a terrific song, as was “Hungry Heart” and a couple of other tunes St. Louis’s AOR station was blasting into the air at the time. But Born … changed everything. What little airtime the songs from Nebraska was getting all but dried up.

It’s a shame, because Nebraska is a remarkable album. I found the darkness highly relatable, as Springsteen and I were both struggling with mental health.+ There’s no denying the pain and pathos Springsteen was channeling through the characters he created to tell the song’s stories. Was it cathartic? I tend to see it as a first step toward Springsteen getting the help he needed.

And therein lies the other lesson: nearly everyone struggles with something. Fame and fortune do NOT make you exempt. More importantly, there are resources available to you 24/7 should you feel the need for help. NO ONE should suffer alone because YOU ARE NOT ALONE. EVER.

In the United States, you need only pick up your phone and dial 988, which is the Suicide and Crisis Hotline. Someone will be there to help you. I’m sure the same services can be found all over the world.

Pain may produce great art, but it’s not a good enough reason to endure it.

Bruce Springsteen got help.

I got help.

You can, too.

^ While it would no doubt have altered his career trajectory, I kind of wish Springsteen had left this song for Nebraska, simply because it would better reveal the song’s actual meaning. Instead, “Born in the U.S.A.” has been distorted into a jingoistic anthem misused by the very people the song rails against. It feels like a waste.

+ Sadly, I was still a good 15 years from having my depression medically diagnosed. I can only imagine what my life would have been had that and the moderate dyslexia I deal with been diagnosed in the early eighties. But that’s the way it goes.

#cirdecsongs

If you would like to have your music reviewed or your band photographed while in Chicago, contact me at cirdecsongs@gmail.com